Key Points

- Understand Network Path Visibility: Traceroute and MTR reveal end-to-end paths, but analysts must distinguish real packet loss from ICMP rate limiting and path asymmetry to avoid false diagnoses.

- Run Multi-Probe and Baseline Tests: Conduct ICMP, UDP, and TCP traceroutes from multiple vantage points to establish baselines, detect congestion, and separate real impairment from cosmetic hop loss.

- Correlate and Validate Results: Cross-check traceroute data with ping, application probes, and MTR to validate user impact and reduce false escalations.

- Document, Retest, and Automate Evidence: Document tests with timestamps and outcomes; automate scheduled traces and artifact collection via NinjaOne to streamline evidence and incident closure.

Traceroute interpretation is necessary for path visibility, but incidents are prolonged by misreading hop loss, mistaking Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) filtering for impairment, or ignoring path asymmetry.

This article demonstrates how to run, read, and verify findings using consistent artifacts. External glossaries and explainers help solidify the basics, while online tools can supplement test preparation.

Steps-by-step guide to interpret traceroute and MTR

To interpret traceroutes, you need to confirm the symptom, establish a baseline trace, run multi-probe traces, interpret hop loss, use latency deltas, account for asymmetry, correlate with adjacent signals, form a hypothesis, retest after a change, and then package evidence.

📌Prerequisites:

- Ability to run ICMP, UDP, and TCP traces from user subnets, core sites, and a cloud vantage point

- Access to My Traceroute (MTR) or pathping on analyst workstations

- A simple evidence template for saving command lines, timestamps, and outputs

- Knowledge of target service IPs and ports, including CDN or anycast endpoints

Step 1: Confirm the symptom and scope

This step saves hours of guesswork by clearly defining the problem.

📌 Use Case: A user in one branch office reports that a web app times out, but others in other locations don’t see the issue. Before tracing packets, the analyst must confirm whether the fault is local, regional, or service-specific.

Document the symptom: what failed, when it started, and who is affected. Obtain the necessary details, such as the application or service name, destination IP address or URL, user location, and access method.

Afterward, check if the outage or slowness is isolated or widespread. Compare results from users, offices, or ISPs to determine if the problem extends beyond a network boundary.

Lastly, establish a baseline for investigation by timestamping the event and defining the “known good” destinations. This context ensures future tracerouts, latency measurements, and provider escalations are interpreted correctly.

Step 2: Establish a clean baseline trace

This step provides a reference point to differentiate between background internet quirks and actual network faults.

📌 Use Case: An analyst investigates slow connections to a cloud-hosted CRM. To verify if the slowdown is new or ongoing, they compare fresh traces from the affected site with baseline results.

A baseline trace is your control sample. From an unaffected site or endpoint:

- Run a standard traceroute and an MTR to the same destination, ideally during normal operating conditions.

- Record the command line, timestamp, and outputs in your evidence template.

- Note stable latency and hop patterns. These represent expected network behavior when the service is healthy.

- Repeat baselines periodically or after significant changes to the provider to keep reference data up-to-date.

Step 3: Run multi-probe traces from the affected path

This step ensures that you see what the users’ traffic actually experiences, not just what responds to ICMP.

📌 Use Case: A SaaS platform seems unreachable from one region. ICMP traceroute stops mid-path, but users can still intermittently reach the site. Running additional UDP and TCP traces reveals that only ICMP is being filtered.

You may miss routing behaviors if you only test with ICMP. To get a fuller picture:

- Run ICMP, UDP, and TCP tracerouts from the affected location to the same destination.

- Record commands, parameters, and timestamps so your results can be reproduced for comparison.

- Save raw outputs in your evidence log to correlate with later retests or provider responses.

Combining probe types reduces blind spots, confirms if packet loss reflects real impairment or just control-plane filtering, and ensures your analysis aligns with the user’s experience of the service.

Step 4: Interpret hop loss without overreacting

This step allows you to distinguish between intentionally limited ICMP replies and actual issues, preventing false alarms and unnecessary escalations.

📌 Use Case: An analyst notices a 40% loss at hop 7 in a traceroute, but the destination still replies cleanly. Instead of flagging a false outage, they recognize it as ICMP rate limiting on an intermediate router.

Traceroute can show packet loss at intermediate hops, but not all loss means data is failing to pass through. To interpret correctly:

- Check if the loss continues beyond the hop. If later hops respond normally, the “loss” is cosmetic. If loss starts at a hop and persists through all following hops, that indicates actual issues.

- Correlate with MTR or ping results.

- Avoid escalating on a single-hop loss.

- Document findings early.

Step 5: Use latency deltas, not single spikes

This step lets you see read latency properly.

📌 Use Case: During an incident review, an analyst sees a sudden 200 ms jump at hop 6, but hop 7 and the destination show normal latency. Instead of flagging congestion, they recognize it as a transient control-plane delay.

When interpreting traceroutes or MTR results, it’s the patterns that reveal congestion. To read latency properly:

- Compare hop-to-hop averages, not isolated peaks.

- A sustained increase that begins at a hop and remains elevated on all later hops usually indicates real congestion.

- A single high reading that does not persist beyond that hop is typically measurement noise.

- Validate with MTR or multiple runs.

- Note the delta along with the number.

- Document where the step occurs.

Step 6: Account for asymmetry and anycast

This step prevents chasing the wrong segment of the network by letting you recognize network paths.

📌 Use Case: A user in Europe reports slowness to a U.S.-based web service. The forward traceroute looks clean, but return traffic takes a congested transatlantic path. Running traces from multiple regions reveals that the issue affects only certain anycast edges.

To avoid misdiagnosis:

- Expect asymmetry. Outbound and inbound routes differ due to policies, peering choices, or traffic engineering by providers.

- Test from different vantage points.

- Run traceroutes from different offices, ISPs, or cloud probes toward the same target.

- Compare hop sequences and latencies to identify if the issue appears consistently.

- Recognize anycast behavior.

- Services like DNS resolvers may terminate connections at different regional nodes using the same IP address.

- Routing can shift during the day due to load balancing, so identical tests conducted at different times may follow other paths.

- Correlate results over time. A consistent fault across diverse vantage points points to a real, stable issue.

- Document observed variations. Record the source vantage point, route differences, and timestamps so others can see if anycast behavior influenced your findings.

Step 7: Correlate with adjacent signals

This step compares traceroute data with other indicators to provide real validation.

📌 Use Case: An analyst sees a 20% loss on a traceroute to a cloud app, but users aren’t complaining. A quick ping test shows no packet loss, and the app responds normally. The “loss” turns out to be ICMP filtering rather than an actual fault.

Traceroute results should always be verified against other data sources to confirm whether they accurately reflect real user impact or merely probe behavior. To do so, you need to:

- Run companion tests with traceroute:

- Ping: Confirms reachability and loss over time.

- Application probe: Tests user functions such as HTTP, SSH, or API calls.

- MTR: Provides visibility into latency and loss trends.

- Compare the patterns:

- If traceroute shows loss but ping and app tests succeed, suspect ICMP filtering or probe rate limiting.

- If loss or latency appears across all tests, the impairment is real and should be investigated.

- Cross-check user symptoms: Confirm if the affected users experience slow responses or disconnection that align with the observed metrics.

- Validate timing: Ensure all tests are timestamped and taken within a short timeframe.

Step 8: Form a clear hypothesis and isolate the segment

This step turns observation into theory.

📌 Use Case: An analyst sees persistent latency starting at the third hop, where traffic leaves the corporate LAN and enters the ISP’s network. They document this as “possible congestion at the site-to-ISP handoff,” including supporting traceroute data and timestamps.

After reviewing your multi-probe traces and corroborating signals, summarize your findings into a statement of where and why the problem occurs:

- Identify the boundary where degradation begins.

- Look for the first hop that shows persistent loss or a sustained latency step.

- Determine if this hop represents a site LAN, ISP edge, transit provider, or destination network.

- Phrase the hypothesis in plain terms.

- Support the hypothesis with evidence.

- Keep it testable.

Step 9: Retest after change or provider engagement

This step validates improvements to confirm that a problem is resolved.

📌 Use Case: After an ISP adjusts a routing policy, an analyst reruns traceroute and MTR tests from the exact locations as before. The new data shows that the 15% packet loss at hop 8 has disappeared, and latency has dropped by 40 ms.

Retest effectively by:

- Re-run the same tests.

- Use the same probe types (ICMP, UDP, TCP), destination, and command syntax.

- Ensure tests originate from the same vantage points as the original capture.

- Timestamp and label results clearly.

- Compare metrics directly:

- Has the packet loss at a specific hop disappeared?

- Did latency or jitter improve, especially for the application’s critical path?

- Summarize improvements.

- Attach evidence to the incident record.

- Confirm with user feedback.

Step 10: Package evidence for closure

This step ensures evidence is packaged and shared.

📌 Use Case: After resolving intermittent latency through a provider fix, the analyst gathers all test logs, before-and-after traces, timestamps, and a summary of the findings. They upload the bundle to the team’s evidence workspace and link it to the incident ticket, providing a transparent record for post-incident review.

To create a complete closure packet:

- Compile relevant artifacts:

- Command line and parameters used for traceroute, MTR, and ping tests.

- Raw outputs and screenshots.

- Timestamps for every test to maintain a timeline.

- Summarize findings:

- The suspected fault segment

- The measurable impact

- The corrective action taken and the outcome

- Include validation data:

- Before-and-after comparison of loss, latency, and route stability.

- User confirmation or monitoring data showing restored performance.

- Store and link evidence properly:

- Save files in your evidence workspace with consistent meaning.

- Attach artifacts to the corresponding incident ticket for visibility.

Best practices when interpreting traceroute and MTR

The table below summarizes the best practices to follow when interpreting traceroute and MTR:

| Practice | Purpose | Value delivered |

| Multi-probe tracing | Avoids ICMP-only blind spots | More accurate path diagnosis |

| Latency step analysis | Localizes congestion reliably | Faster fault isolation |

| Persistence check | Filters cosmetic hop loss | Fewer false escalations |

| Multi-vantage testing | Handles asymmetry and anycast | Correct scope and ownership |

| Evidence packets | Clear story for tickets and QBRs | Faster closure and accountability |

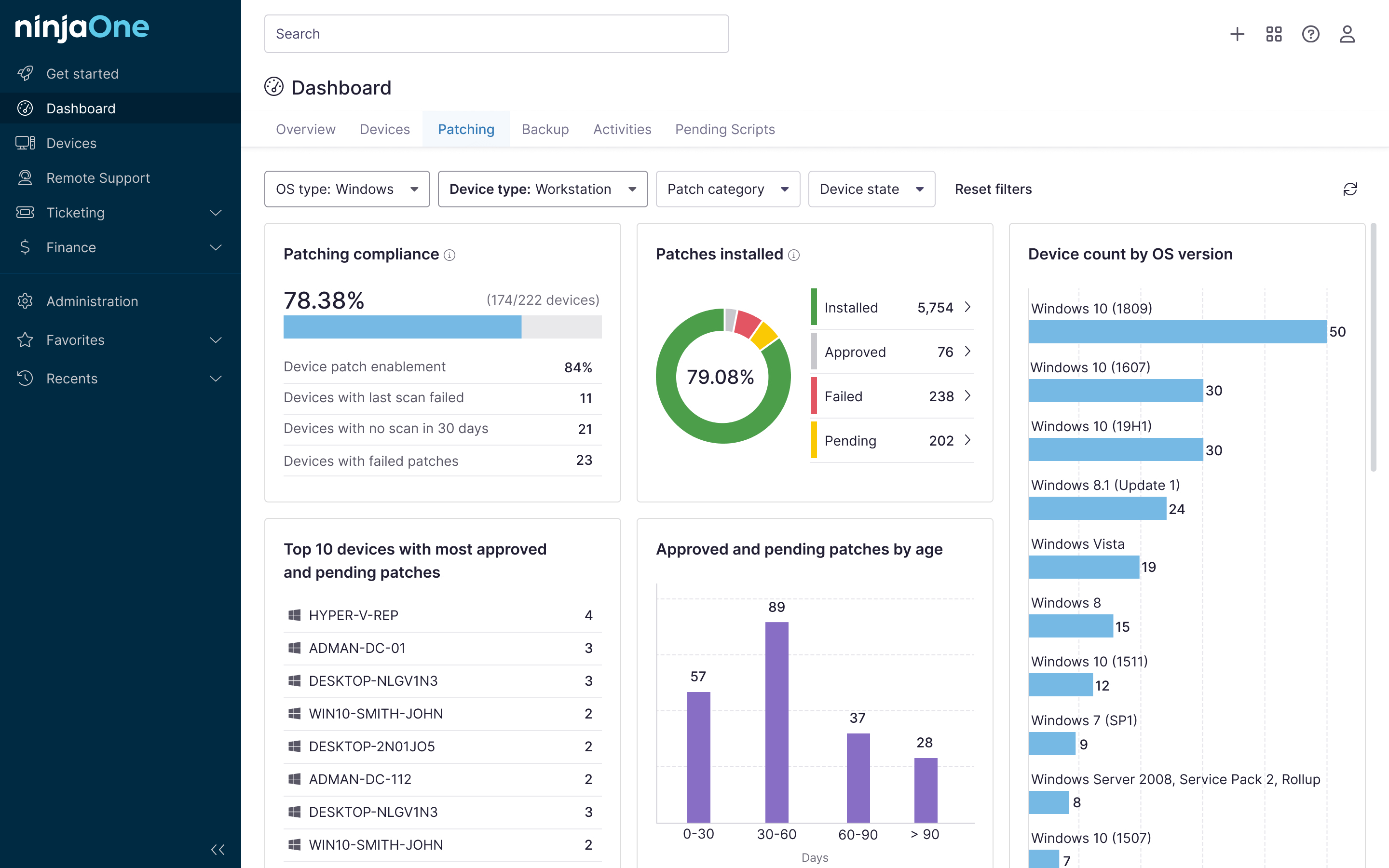

NinjaOne services that help interpret traceroute and MTR

You can use NinjaOne’s scheduled tasks to run traces from representative endpoints, collect outputs centrally, and tag artifacts by site and Internet Service Provider (ISP). You can also attach evidence to incident tickets, allowing managers to demonstrate improvement.

Interpret tracerouts like an operator

Traceroute is more useful when you treat it like a network operator. Testing different probe types, looking for consistent patterns, understanding how modern routing works, and saving clear evidence lets you find problems faster and resolve tickets more confidently.

Related topics: